Corby Kummer, executive director of Food & Society at the Aspen Institute, senior editor at The Atlantic, and a senior lecturer at the Tufts Freidman School of Nutrition Science delivered the commencement address at Boston University Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences on May 19, 2024. He addressed undergraduate and graduate students from the Sargent Class of 2024 earning degrees in health disciplines including health science, human physiology, nutrition, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech, language & hearing sciences.

Good morning! Let me be the first to take Dean Dennerlein’s wise advice always to say thank you, by thanking him, the Sargent convocation committee, and Boston University for giving me the honor of meeting you. And I get to sit next to the valedictorian, Brianna Spiegel—congratulations!

Photo credit: Jake Belcher for Boston University

Your degrees are a huge achievement that merit huge congratulations. I may teach master’s students at a school called the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Food Policy (about the same number of syllables as the Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences) but I only have a BA, and it was in English. Bachelors of science are hard! So are master’s degrees! Ph.Ds are really hard! They take time! That makes you all incredibly impressive, and it’s an honor to get to talk to you.

It’s students like you who can change the world for the better, who have the tools to improve life for both individuals and entire populations. You’re the people I get to teach. You’re the people who can be a part of the food policy program I created at the Aspen Institute, Food & Society—a program dedicated to making significant change in food systems toward equity and sustainability.

What an English degree did equip me to do was spend several decades as a restaurant critic. To most people that sounds like a dream job, and it was fun—especially being able to treat friends who otherwise wouldn’t have access to fancy meals. And, at least in the days before online took over print, somebody else paid the bills. You eat some great food and a lot of bad food. As a critic, you’re focused much more on observing everything happening in the room and guessing what’s happening behind the scenes than you are on what’s on your fork. Food makes for good stories, and most often it’s made by good people—people who want to create families and communities through food, and leave them feeling better.

I started writing more and more about nutrition and how to make the most widely available and affordable food promote better health. I found people to admire—executives and scientists who worked for global corporations that have the potential to make change on a global scale. And I found dedicated, warmhearted, inventive people from grassroots organizations who were improving food in underserved communities against formidable odds.

Years of interviewing these mission-driven people made me think how much more significant their work could be if they came together to share ideas and share their core values and hopes. Bringing people together who might not be like-minded but who do share common ideals is exactly what the Aspen Institute does. Creating a program there seemed a much better long-term road to making long-term change than writing one-off articles, as fun and gratifying as it was to write, say, cover stories on pasta and bottled water for The Atlantic and the New York Times Magazine, a regular cooking, restaurant, and nutriti0n column in The Atlantic, and pieces in Vanity Fair.

Years of interviewing these mission-driven people made me think how much more significant their work could be if they came together to share ideas and share their core values and hopes. Bringing people together who might not be like-minded but who do share common ideals is exactly what the Aspen Institute does. Creating a program there seemed a much better long-term road to making long-term change than writing one-off articles, as fun and gratifying as it was to write, say, cover stories on pasta and bottled water for The Atlantic and the New York Times Magazine, a regular cooking, restaurant, and nutriti0n column in The Atlantic, and pieces in Vanity Fair.

Food touches on everything important in life. As you’ve certainly heard, social determinants of health are a part of every current theory of what leads to improved public health. Housing, transportation, and food access are perhaps the holy SDOH trinity. I’m prejudiced. I hope that if it comes to a choice of which determinant you’ll work on, you’ll all choose food. Not just because I like and admire the people who make care about food but because health sciences equip you to interpret and implement nutrition data.

This is commencement, so I shouldn’t ask for a show of hands on anything except how proud you and your families are that you’re graduating. I will ask, though, how many of you took Sargent courses in nutrition and metabolism, and how many are thinking of making healthful diets a part of their careers. Hands? Okay. It’s my mission to persuade more of you to make food and diet integral to whatever you practice.

Why? Because along with maternal and early childhood health care, nothing matters more to future health than a healthful diet. Look at the grim statistics during Covid. Underlying illness, much of it caused by poor eating habits, led to dramatically elevated rates of illness and death, particularly in Black and Latino populations. Today, more than 350,000 annual deaths from cardiovascular disease are attributable to poor nutrition. Identifying how dietary interventions can meaningfully influence individual and population health, then, is a national priority. It’s clear that widespread access to–and enthusiasm for–a healthier diet will make a healthier population.

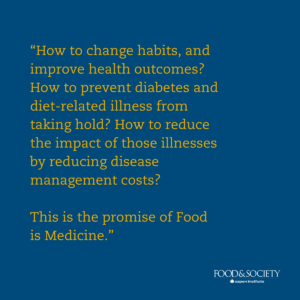

How to change habits, and improve health outcomes? How to prevent diabetes and diet-related illness from taking hold? How to reduce the impact of those illnesses by reducing disease management costs? This is the promise of food is medicine. It’s a field I’ve devoted most of my adult life to, first as an admiring onlooker and cheerleader at Community Servings, a Boston grassroots organization that is now a national leader in food is medicine, and then as an active program leader at Food & Society at the Aspen Institute.

How to change habits, and improve health outcomes? How to prevent diabetes and diet-related illness from taking hold? How to reduce the impact of those illnesses by reducing disease management costs? This is the promise of food is medicine. It’s a field I’ve devoted most of my adult life to, first as an admiring onlooker and cheerleader at Community Servings, a Boston grassroots organization that is now a national leader in food is medicine, and then as an active program leader at Food & Society at the Aspen Institute.

Community Servings started in 1989, a time when HIV activists were tipping the balance of control to the hands of patients. The way that many of us who were not medical professionals found to help—and to fight our own sense of helplessness–was food. The original impulse of Community Servings, of which I was a founding board member, was to involve Boston’s best chefs in designing menus for people facing a life-threatening illness. From-scratch meals delivered to the door of patients who were isolated and frightened, Community Servings workers and volunteers brought clients aid and comfort–the name of a benefit evening at the TD Garden that gave rise to Community Servings. Julia Child even came, and I’m pretty sure I was her designated driver that night–I saw a lot of her in those days, and she was game to attend. It was a little out there to support HIV causes then. The event showed the power of community action and cohesion in a time when there were no easy answers.

Aid and Comfort was my first taste of asking people who had worked hard to make a name for themselves bringing good food to others to help people in need. Boy, did they want to help. As I would see decades later at Food & Society when forming a group of restaurant owners and chefs who wanted to protect workers during Covid, something we did together with Jose Andres and the country’s large and small restaurant groups, food people are generous. They care about community.

Photo by Jake Belcher for Boston University Photography

The missing piece was a research-backed plan for healthful diets, and which foods would bring the most significant improvement to patients who had which combination of health needs. When David Waters, who has been CEO of Community Servings for going on 30 years, took leadership of the agency, he understood that chefs had to be as skilled in understanding nutrition as a form of health care as they were making palatable and culturally appropriate meals people would eat.

The insights and practices of meals designed to improve patient health could apply to a wide number of illnesses and conditions beyond HIV, which at last was being brought under control by new drugs. So the next step was to solidify a nexus to the health care system. That’s the core definition Food & Society uses for our Food is Medicine Research Action Plan. Formal ties to health care systems are what will keep the field of food is medicine alive and growing, and will broaden client and patient eligibility for meal reimbursement—the case that research into food is medicine makes.

Understanding a client’s full range of health care needs, and being sure they can get meals to make and keep them well, is what advocates want to see baked into all health care payer criteria. How to move beyond the promising but ultimately limited world of pilots, which is where current large-scale food is medicine provision takes place? Wide-scale research. Wide-scale program evaluation using common metrics.

That’s what made Food & Society spend going on five years writing our Research Action Plan. With the collaboration of a brilliant team, we assembled all the peer-reviewed research in medically tailored meals, medically tailored groceries (promising, boxes of groceries and meal kits), and produce prescriptions. In easy-to-follow charts and visualizations—data visualization, as you know, is a key to making health concepts understandable and actionable—we show which interventions have the strongest effects on health indicators like A1c levels, Type 2 diabetes management, hypoglycemia, and overall nutrition security.

That’s what made Food & Society spend going on five years writing our Research Action Plan. With the collaboration of a brilliant team, we assembled all the peer-reviewed research in medically tailored meals, medically tailored groceries (promising, boxes of groceries and meal kits), and produce prescriptions. In easy-to-follow charts and visualizations—data visualization, as you know, is a key to making health concepts understandable and actionable—we show which interventions have the strongest effects on health indicators like A1c levels, Type 2 diabetes management, hypoglycemia, and overall nutrition security.

The first peer-reviewed food is medicine research showed dramatic decreases in emergency-room visits and diabetes and other disease management costs—the data that payers most want to see. That’s over the short term, the term payers work in. But the winning long-term argument for food is medicine is what happens in the long term: encouraging eating habits from infancy onward that will prevent diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. And the sticky truth is that the ROI for prevention, and simply giving more food to people who need it, is hard to show in the periods payers and politicians want to see—even if the benefits to society will last for generations.

We’re fortunate that our Food is Medicine Research Action Plan has become the standard reference for providers and agencies getting into the field, and that the National Institutes of Health quoted from it in its concept for Food is Medicine Centers of Excellence. The NIH even embedded our recommendations for making equity a part of research design, implementation, and evaluation into their own recommendations.

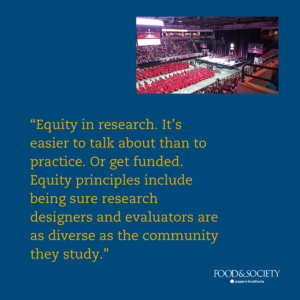

Equity in research. It’s easier to talk about than to practice. Or get funded. Equity principles include being sure research designers and evaluators are as diverse as the community they study. Another goal I feel particularly strongly about is staying involved with study participants after the implementation phase of a study is finished. I call this the What happens when the circus leaves town problem. A plan for maintaining access to healthier food, the ability to cook and use it, and continued access to the kind of counseling and healthcare that are part of rigorous studies is an obligation researchers know about and want to honor. But it’s not an obligation they’re usually funded to offer.

Equity in research. It’s easier to talk about than to practice. Or get funded. Equity principles include being sure research designers and evaluators are as diverse as the community they study. Another goal I feel particularly strongly about is staying involved with study participants after the implementation phase of a study is finished. I call this the What happens when the circus leaves town problem. A plan for maintaining access to healthier food, the ability to cook and use it, and continued access to the kind of counseling and healthcare that are part of rigorous studies is an obligation researchers know about and want to honor. But it’s not an obligation they’re usually funded to offer.

There’s huge promise. An exciting new crop of researchers and agencies are entering the field. The next phase of our work at Food & Society—a best practices guide to starting food is medicine work in community-based organizations and food banks—will excitingly introduce us to more of them. Like you!

Engaging communities is what brings real health, and what I hope will motivate you as you travel from job to job. Which community? Start small. Get involved, whether or not you make food access your own cause. Look for a community to join. Eventually, with a good experience or two behind you, if you don’t see the ideal community you’d like to join, you’ll build your own. That’s what we’ve done at Food & Society, where in addition to our other initiatives we’ve created the Food Leaders Fellowship, which every year brings together 18 leaders from all parts of the food system bent on making change toward sustainability and equity.

There’s plenty more to do. Looking for problems? Why are ultra-processed foods strongly correlated with obesity and poor health? The actual scientific mechanism is yet to be found. Policy? Protect SNAP recipients when scammers steal information from their EBT cards and drain their accounts. Those are just two examples from the past month’s news. Expand WIC benefits for young parents and families, the country’s first and most effective food is medicine program but one under current threat. Make healthful school breakfasts and lunches available free to all children—as Boston and Massachusetts have been way ahead of the curve doing. Or work to do what successive presidential administrations couldn’t get done: force food makers to significantly reduce the sodium in their foods, not just obvious examples like soup but the places sodium hides, like bread and baked goods.

Even if you don’t have core interests related to food and don’t find a job right away—volunteer. You might just find a life partner. It worked for me: in Community Servings’s early years I constantly heard about John Auerbach, who began the first AIDS bureau at a state health agency, and later became commissioner of health for Boston and then Massachusetts. He too was a founder of Community Servings, but not on the board, and we didn’t overlap until the day we met at an awards lunch more than 25 years ago. We’ve been together ever since. His insights about how to make conditions healthier and health care accessible to everyone are my inspirations in my professional and personal life.

Even if you don’t have core interests related to food and don’t find a job right away—volunteer. You might just find a life partner. It worked for me: in Community Servings’s early years I constantly heard about John Auerbach, who began the first AIDS bureau at a state health agency, and later became commissioner of health for Boston and then Massachusetts. He too was a founder of Community Servings, but not on the board, and we didn’t overlap until the day we met at an awards lunch more than 25 years ago. We’ve been together ever since. His insights about how to make conditions healthier and health care accessible to everyone are my inspirations in my professional and personal life.

So there all kinds of uses you can put your shiny new degree to work doing! Finding work, unpaid or paid, with a group whose mission inspires you will bring you in contact with a community of people who care about what you do, and new ideas of how you yourself can make change. If you find a place that lets you learn and grow and builds your self-respect, even if it’s not directly on the path you laid out for yourself, stay there. And did I say wear sunscreen? Wear sunscreen.

My many congratulations to all of you on the discoveries, unexpected turns, and increasing ability that await you to turn ideals and science into action.